'Our house is on fire': Suburban women lead Trump revolt

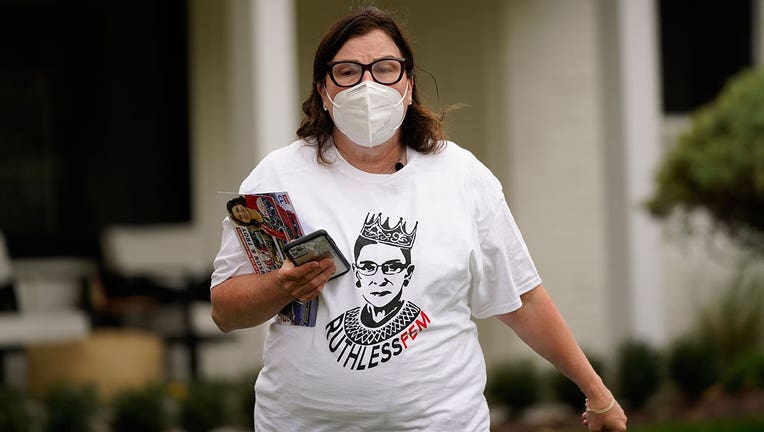

Lori Goldman canvasses in Troy, Mich., Thursday, Oct. 15, 2020. For most of her life, until 2016, Goldman had been politically apathetic. Had you offered her $1 million, she says, she could not have described the branches of government in any depth.

TROY, Mich. - For most of her life, until 2016, Lori Goldman had been politically apathetic. Now every moment she spends not trying to rid America of President Donald Trump feels like wasted time.

“We take nothing for granted,” she tells her canvassing partner. “They say Joe Biden is ahead. Nope. We work like Biden is behind 20 points in every state.”

Goldman spends every day door knocking for Democrats in Oakland County, Michigan, an affluent Detroit suburb. She feels responsible for the country’s future: Trump won Michigan in 2016 by 10,700 votes and that helped usher him into the White House. Goldman believes people like her -- suburban white women -- could deliver the country from another four years of chaos.

For many of those women, the past four years have meant frustration, anger and activism — a political awakening that powered women's marches, the #MeToo movement and the victories of record numbers of female candidates in 2018.

That energy has helped create the widest gender gap in recent history. It's started to show up in early voting as women are casting their ballots earlier than men. In Michigan, women have cast nearly 56% of the early vote so far, and 68% of those were Democrats, according to the voting data firm L2.

That could mean trouble for Trump, not just in Oakland County but also in suburban battlegrounds outside Milwaukee, Philadelphia and Phoenix.

Trump has tried to appeal to “the suburban housewives of America,” as he called them. He has argued that Black Lives Matter protesters will bring crime, low-income housing will ruin property values, suburbs will be abolished. Campaigning in Pennsylvania last week, he begged: “Suburban women, will you please like me?”

There's no sign all this is working. Some recent polls show Biden winning support from about 60% of suburban women. In 2016, Democrat Hillary Clinton won 52%, according to an estimate by the Pew Research Center.

Goldman started her group, Fems for Dems, in early 2016 by sending an email to a few hundred friends that said she planned to help elect the first female president and asked if they’d like to join her. Four years later, their ranks have swelled to nearly 9,000.

There is one thing Goldman gives Trump credit for. He stormed into the White House on pure guts and bombast, unwilling to acknowledge failure, averse to saying sorry. Those are not natural traits for most women who’ve absorbed societal expectations to please and be polite, she says.

But she is terrified that the constant cycle of crises has left many women exhausted and that could stall this leftward lurch. The nation is reeling from a pandemic and protests, the death of a revered Supreme Court justice, the hospitalization of the president, a foiled plot to kidnap Michigan’s governor.

“Our house is on fire,” Goldman says, and so she steers her SUV to the next door on the cul de sac.

Oakland County stretches from the edge of Detroit more than 30 miles. Although Clinton won here in 2016, she won fewer votes than Barack Obama four years earlier, while the third-party vote soared.

But in 2018, some political scientists described it as the epicenter of a major political shift as women turned on Republicans.

“Women are pragmatic voters,” said Michigan’s Democratic governor, Gretchen Whitmer. “We care about our kids. We care about our parents. We care about economic security. And so candidates who stand up for those values and show that they can be good, decent human beings is something I know resonates. And I think this moment, with this White House, that is more acute than ever.”

Whitmer nearly doubled Clinton’s margin in Oakland County in 2018. That same year, Democrat Elissa Slotkin flipped a congressional seat that was under Republican control for almost 20 years.

Some of Slotkin’s strongest supporters were Republican women.

Nancy Strole, a longtime elected township clerk in the rural northern part of the county, had not been able to bring herself to vote for Trump. She considers herself an “old-fashioned kind of Republican.” She hasn’t changed, she said — her party was “hijacked.”

“It’s not just Trump,” she said. “It wouldn’t happen unless there are others who acquiesced and were willing to go along with it either by their silence, by their lack of will, by their lack of courage.”

Andrea Moore, by contrast, was raised in a Democratic family. But she voted for Trump because she was fed up with career politicians who seemed interested only in money and power.

“He was an unknown quantity, but now we know,” said Moore, 45, who lives in a suburban community in Wayne County.

She can’t remember the precise moment she decided she’d made a mistake. It felt like a toxic relationship: You can make excuses for a while, but eventually disgust settles in.

She can’t understand how anyone could support Trump after his response to his own bout with COVID-19 — how he flouted masks and held rallies, downplayed the threat, failed to acknowledge that he had access to treatments that others don’t, she said. All after more than 215,000 Americans died.

Moore, a stay-at-home mom who home-schools her 9-year-old son, doesn’t love Biden. But if the choice is between Trump and anyone else, she said, anyone else will do. She hopes the administration will be driven by Kamala Harris — a Black woman, the child of immigrants, young, sharp.

“It’s been an old white guy’s game for way too long,” Moore said.

Trump’s pitch to try to reclaim suburban female voters relies on an airbrushed version of America’s past. He has warned that “Biden will destroy your neighborhood and your American dream.” He revoked an Obama-era housing initiative meant to curtail racial segregation, claiming that property values would diminish, crime would rise and suburbs would “go to hell.”

“I think if this were 1950, his message would be perfect,” said Karyn Lacy, a sociologist at the University of Michigan. “The problem is it’s not 1950.”

___

Associated Press journalists David Eggert, Hannah Fingerhut, Emily Swanson and Angeliki Kastanis contributed to this report.